The Dominican Republic has expelled thousands of Haitians who sought economic opportunity

Queer Haitian migrants who’ve been deported from the neighboring Dominican Republic, rejected by both sides due to homophobia and racism, face a fraught future as they search for dignity and economic opportunity.

One organization, Héritage pour la Protection des Droits Humains (Heritage for the Protection of Human Rights), has been working with migrants in the northern Ouanaminthe region – where deportees are repatriated from the Dominican Republic, often without money, possessions, or identity papers and often fair from where they may have previous ties on the island – helping them reintegrate in Haiti. Until recently, it provided an inclusive emergency shelter for displaced persons.

Erasing 76 Crimes spoke to Héritage staff and volunteers about the the situation on the ground, and why queer Haitians need more support.

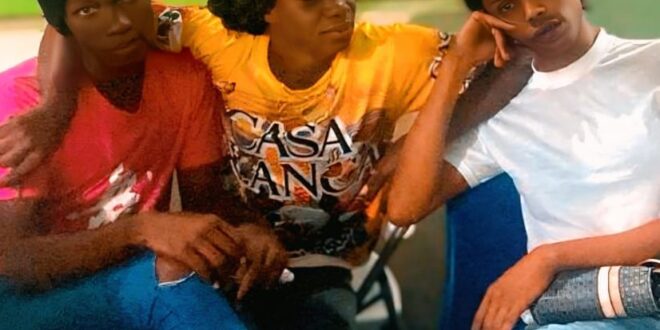

Non-binary and transgender young people, expelled from the Dominican Republic and welcomed at the premises of the Heritage for the Protection of Human Rights (HPDH) association in Ouanaminthe (Photo courtesy of @merlinjean)

Merlin Jean (director): There are rushed deportations of people expelled from the Dominican Republic who leave behind everything they have built there over the past 20 or 30 years. Some had already started families there, and often the Haitian men who are taken back to the border leave their wives and children behind.

No one is spared, not even pregnant women or those who have just given birth, who are forcibly removed from hospitals without postnatal care. Minors are part of the collective convoys that are brought back to the Haitian side of the border every day, while day after day, stone by stone, the gigantic wall the Dominican president wants takes shape, in order to seal off any porosity between the societies of the two countries that share the island of Hispaniola.

It is a silent humanitarian crisis. Haitian transgender people detained in single-sex cells by the Dominican authorities are particularly vulnerable, as are people living with HIV who do not have access to continuity of care for antiretroviral drugs in detention centers in the neighboring country.

For those who have been brought against their will to Ouanaminthe, the only open entry point on the Haitian-Dominican border, the needs are immense, especially since they are often not necessarily from northern Haiti. In addition to food, these people need accommodation before they can eventually return to other Haitian departments where they have ties, which requires financial resources that these displaced persons lack. Most of these people no longer have any identity documents, as the Dominican police throw away their belongings.

When they arrive at our premises, we assess whether they need for psychological support. This is almost always the case, as we receive people who have been injured and mistreated during their arrest against a backdrop of racism and xenophobia in the Dominican Republic.

In any case, living in Haiti represents another security challenge for those deported from the neighboring country, due to the state’s security failures and the presence of armed gangs.

In general, we deplore the lack of a national policy for the reception and economic reintegration of forcibly repatriated persons, as these workers in the Dominican Republic often played a decisive role in the Haitian countryside by sending money to their elderly relatives.

In these circumstances, our association is on the front line of the crisis and we have to cope with limited resources, particularly in terms of accommodation capacity at the Charlot Jeudy shelter (Editor’s note: the shelter is named after a Haitian activist who was assassinated in November 2019).

Mildred Semerant (social worker): Between October 2024 and early April 2025, our organization experienced sustained activity with nearly 1,392 displaced persons taken in, 369 of whom self-identify as LGBT+.

Haiti on the left in blue and Dominican Republic on the right in red (Illustration courtesy of @maps.and.maps)

Creating an inclusive space in a transit area

Erasing 76 Crimes: In practical terms, How do you manage the care of displaced persons and the cohabitation and coexistence of people of different sexual orientations and gender identities?

Orphée (volunteer): We mainly receive adult men who do not live as couples at the Charlot Jeudy Center accommodation facility.

We therefore inform the displaced persons in advance not to discriminate against transgender or gay people when they enter our premises. Sometimes, it is necessary to remind them of the rules for the well-being of all, because we have a duty to provide a space of care and well-being for the people we welcome, especially transgender people.

Generally, after the first night, things settle down and the initial reluctance of the returnees dissipates. Nevertheless, here and there in town, people spread nonsense to dissuade some from finding rest in our accommodation, alleging insane rumors of same-sex rape.

People who are just passing through Ouanaminthe stay with us for an average of one to two nights, while for others, within the limits of our capacity, we offer the possibility of a 45-day stay, renewable once.

For hygiene, displaced persons are given a kit thanks to the support of the International Organization for Migration, while we try to offer hot meals on an ad hoc basis. Finally, for screening or serological testing of people living with HIV, we refer our users to the nearest health centers. The recent cuts in US funding are having a severe impact, but the Foundation for Reproductive Health and Family Education is working on the ground to mitigate the effects with the United Nations Development Program.

For people who cannot return to Port-au-Prince, which is controlled by gangs, or return to the Dominican Republic, we are in a space, a territory of waiting. (Editor’s note: since October 8, 2025, Héritage pour la Protection des Droits Humains has stopped housing displaced persons).

The Charlot Jeudy Shelter is always busy. (Photo by @merlinjean).

The specific situation of LGBT+ people repatriated to Haiti

Jesula Blanc (lawyer living in Canada): People who are forcibly repatriated and belong to the LGBT+ community face strong rejection upon their return to Haiti.

Stigmatization and insecurity hinder the relocation process for trans and non-binary LGB people. These are real difficulties that add to the glaring lack of family support in a country where economic resources are scarce.

We are dealing with people who need to rebuild their identity while readjusting to Haitian reality. Psychological support is essential.“

See Also

Mildred Semerant (social worker): To add to what was said earlier, since 2022, we have recorded more than 200 victims of gender-based violence. This is why we do not publicize the facility in public spaces. And we do not openly advertise that we are a refuge for LGBT+ people in distress.

However, when displaced persons come to us, at the time of registration, we make sure to specifically ask about the gender identity of the people we are assisting.

Jesula Blanc (lawyer living in Canada): There is still a need to further develop emergency humanitarian aid for LGBT+ people, as the need for permanent and secure accommodation is particularly acute among this group.

In addition, the existing provision of sexual health care for men who have sex with men (MSM), transgender people, and people living with HIV should be strengthened.

Merlin Jean (director): Ouanaminthe is adjacent to the international market of Dajabon on the Dominican side, which employs a cheap and hard-working Haitian workforce. But in order to work there, you must have an identity card, a document that most of the people we help no longer have.

Given the saturation of the job market, the development of microcredit for the LGBT+ community could create a lever to start small income-generating activities, so that no one is left behind. At the same time, it could help to boost the self-esteem of the beneficiaries of this type of scheme.

Social workers seek to identify the needs of displaced persons (Photo by @merlinjean).

Erasing 76 Crimes: How do you see the future between Haiti and the Dominican Republic?

Orphée (volunteer): We are on the same island. These two nations, Haiti and the Dominican Republic, are destined to coexist for life.

Merlin Jean (director): We need to strengthen dialogue between our two societies via digital networks, given the wall that now exists between the two countries.

We must try to organize the management of migration flows upstream, because Haitians continue to try to go to the Dominican Republic because they have no choice.

As the director of an NGO on the front line of this crisis, I believe that a national program should be put in place to reintegrate those who have been deported, while putting displaced persons at the center of the process, in order to successfully reintegrate them into Haitian society. Obviously, this also requires support for the associations on the front line that are receiving people in difficulty.

Xavier Radio Ug News 24 7

Xavier Radio Ug News 24 7